BBC

BBCThe last time Oasis played Wembley Stadium, in 2009, a standing ticket cost exactly £44.04.

For their return next summer, the same ticket was priced at £150. Vastly more than the old ticket price which, when adjusted for inflation, would cost £68.

Not only that, but some fans were charged hundreds of pounds more than the face value, after so-called “dynamic pricing” boosted the cost in response to high demand.

But Oasis aren’t alone. If you’ve logged onto Ticketmaster over the last couple of years, you’ll know the cost of live music has soared.

Ticket prices shot up by 23% last year, having already risen 19% since the pandemic. Going to a gig can cost the same amount as taking a holiday, and prices are only rising.

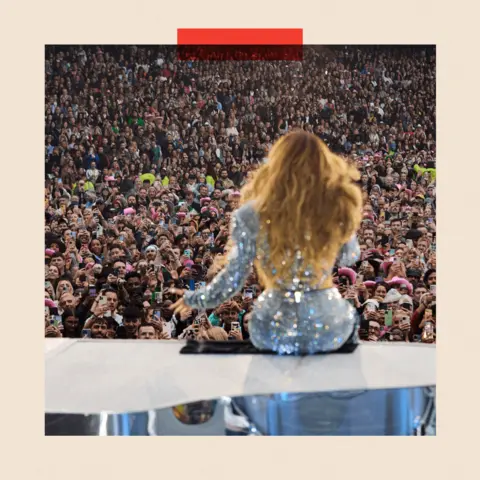

At the most extreme end of the scale, Madonna charged £1,306.75 for VIP passes to her Celebration tour; and Beyoncé offered fans the chance to sit on the stage of her Renaissance concerts for the bargain price of £2,400.

Overall, the average ticket price for the top 100 tours around the world was £101 last year, up from £82 in 2022, according to Pollstar, a trade publication that tracks the concert industry.

In the UK, 51% of people say high prices have stopped them going to gigs at least once in the last five years. Among 16 to 34-year-olds, two-thirds of concert-goers say they’ve reduced the number of shows they attend. But despite this, tours with high-priced tickets keep selling out – but only for the biggest-name artists.

Abbi Glover, 33, from New Holland, Lincolnshire, said the cost of tickets “creates a divide” between those who can afford them and those who are “priced out”.

“I work hard and earn a decent wage. What do I have to do to be able to just enjoy these things when I’m doing everything I possibly can?”

‘Milking the cow’

UK prices are still below those in the US but, as ticketing expert Reg Walker told the BBC, “what happens there happens here five to 10 years later”.

So why have costs skyrocketed?

If your first thought was “greed”, well, that’s definitely part of it.

“It’s not speculation to think that some artists want to make as much money as they can,” says Gideon Gottfried, Pollstar’s European editor.

One musician who’s been bullish about the price hikes is Bruce Springsteen.

Fans were alarmed when some seats for his 2023 US tour were priced as high as $5,000 (£3,874), thanks to Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing.

Speaking to Rolling Stone, Springsteen argued that most of the tickets were in an “affordable range”, but he was fed up with touts making money off his back, so he chose to match their prices.

“I’m going, ‘Hey, why shouldn’t that money go to the guys that are going to be up there sweating three hours a night for it?’” he said.

Kiss star Gene Simmons also defended the system.

“Whatever the pricing is, it’s all academic,” he told Forbes. “Somebody sits in a room and tries to figure out how far the rubber band can stretch. And if you’re not selling tickets, guess what happens? The price goes down. Capitalism!

“Vote with [your] money,” he concluded. “You don’t like the ticket pricing? Don’t buy a ticket.”

Springsteen and Simmons are in good company. Other artists who’ve embraced dynamic pricing include Coldplay, Harry Styles, Olivia Rodrigo and Taylor Swift (although she ditched it for the Eras tour after significant fan backlash).

Following the Oasis debacle, Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer vowed to get a “grip” on the situation and “make sure that tickets are available at a price that people can actually afford”.

But it might not be so simple…

Aside from the lure of a big payday, there are many reasons why artists are charging more.

Some are trying to combat the impact of streaming – the majority of musicians make just 5% of their income from streaming, a sharp decline from the years when vinyl and CD were king.

Others are worried about their longevity, in an era when entire careers can be measured in the span of a TikTok trend.

“Nobody really knows what the heck is going on, and how the economy will develop and what the next crisis is going to be,” says Gottfried, “so some artists are trying to milk the cow as much as possible, while it’s still possible.”

Not everyone thinks that way. Punk-pop star Yungblud organised his own festival in Milton Keynes this August, setting prices at a market-beating £49.50.

He was compelled to take action after noticing unsold seats on his US arena tour last year.

“Five hundred seats would be completely empty because they were $200 a ticket,” he told Music Week. “I’d have 1,000 kids outside the venue who couldn’t afford to come in and I was like, ‘Something’s got to change here.’”

But the festival didn’t go completely to plan. Heightened security after a stabbing in Milton Keynes the previous weekend led to delays of up to three hours for fans waiting to get into the venue. As temperatures soared above 30 degrees Celsius, some passed out in the queue. Others gave up and went home.

Higher-priced tickets could have paid for extra security staff and eased those pressures – illustrating the delicate balance that has to be struck when setting prices.

Still, Yungblud isn’t the only one trying to get a fair deal for concert-goers.

Paul Heaton capped prices for his upcoming tour at £35. Pop star Caity Baser set her 2023 concerts at just £11 – or “two meal deals”, as she put it – to help cash-strapped fans.

But these artists don’t require big productions full of pyrotechnics and jumbotron video screens.

For acts who do, the cost of touring has spiralled since the pandemic. Here are just a few examples:

- Transport Whether you’re in a minivan or a private jet, it costs more to travel these days. Fuel prices have risen by 20% since 2019 and a shortage of drivers post-Brexit means experienced crew can charge a premium.

- Freight costs A tour isn’t just about moving bodies – for big arena and stadium shows, the stage also has to be transported. According to the pop star Lorde, the cost of shipping her stage around the world increased by up to 300% after Covid. And logistics company Freightwaves says the cost of insuring one truck can be as high as $5m (£3.8m). For context, Taylor Swift’s Eras tour requires up to 50 trucks.

- Catering We’ve all seen our food bills increase, and touring artists are no exception. When you have hundreds of mouths to feed, the costs add up.

- Stage equipment From sound systems to lighting rigs, rental costs for tour gear have risen by 15-20%. And with more tours on the road, equipment is overbooked – which can push prices even higher.

“We’ve seen projects where the cost of overheads have increased by up to 35 to 40%,” says Stuart Galbraith, CEO of concert promoters Kilimanjaro Live, “and the only form of income that comes in to cover all of that is ticket money”.

Even when prices go up, the profit margins are minimal, according to Stephan Thanscheidt, CEO of FKP Scorpio, which organises more than 20 European festivals, as well as tours by Ed Sheeran, the Rolling Stones and Foo Fighters.

“The costs associated with our productions have doubled or tripled [but] we cannot and will not compensate for this by tripling the ticket prices,” he told Pollstar last year.

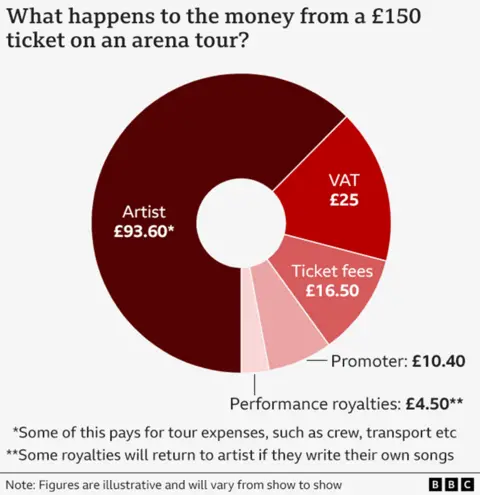

That means the artist’s share of the box office – roughly 56% of the money you pay – increasingly goes towards production costs, not profits.

The squeeze is particularly tight on UK festival organisers, which have also been hit by a ban on “red diesel”, a fuel tinted with red dye, which they previously used to power the generators and heavy vehicles needed to construct festival sites.

The move is part of the UK’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gases, and meant some organisers suddenly had to pay a higher rate of fuel duty from April 2022 – a big increase of 46 pence per litre.

Since then, the average cost of a UK festival ticket has shot up by 22%. Combined with other rising costs, more than 50 festivals went on hiatus or closed completely this summer.

The teetotal tax

Small venues are under pressure, too. Their prices might average between £7 and £10, but they’re struggling to sell shows – partly because fans have already spent their money on stadium tickets that cost the same as a games console.

Toni Coe-Brooker from the Music Venues Trust said this is down to “a culture in which people think that grassroots gigs should be free”.

In the past, that didn’t matter because owners made plenty of money behind the bar. But Gen Z are increasingly turning their backs on alcohol. One study says 26% of 16-to-25-year-olds are teetotal, and that leaves yet another hole in venues’ finances.

Combined with other pressures including higher rent and electricity bills, 125 music venues closed or stopped hosting live music in 2023.

In those that remain, costs are so tight that “a lot of venue operators aren’t even paying themselves, which is really worrying,” says Coe-Brooker.

The Music Venue Trust wants bigger concert halls to donate £1 from each ticket sold to the grassroots scene and the next generation of artists.

That wouldn’t necessarily push prices up again – the trust says the £1 fee would be factored into existing costs – but here’s the fascinating thing: If the artist is the right one, fans will pay regardless.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLive Nation is the world’s biggest concert promoter and it shifted a record 118 million tickets in the first six months of 2024.

According to its latest earnings report, sales for arenas, amphitheatres, theatre and club shows are all up double digits.

“People’s enthusiasm to go out has not been as curbed as we expected in the current economy,” says Gottfried.

“VIP ticket sales have definitely picked up. Every single promoter I’ve spoken to across the individual European markets, has seen an uptake in almost every case. And £1,000 for a VIP package is not at all unheard of.”

‘Outrageous money’

However, the same rules don’t apply to everyone.

The biggest names might get away with charging hundreds of pounds per show, but “the weaker tours are coming under more pressure,” says Galbraith.

In other words, with an ongoing squeeze on their disposable incomes, fans are cutting back on experiences that don’t seem unique or essential.

“We’re competing in a marketplace that isn’t just gig to gig,” says Galbraith. “It’s also, are we value for money versus a restaurant? Are we value for money versus a mini break? So every tour has to be as cost effective as they possibly can.”

There are some signs that we’ve reached a peak. Jennifer Lopez and the Black Keys both scrapped recent US arena tours, after fans baulked at average prices of around $150 (£116). And the most expensive tickets for Billie Eilish’s 2025 UK tour (£398, of which £151 goes to local charities) are still available, months after going on sale.

It’s hard to say whether this will change. But Leah Rafferty, 27, from Sheffield, is an example of a fan who will pay whatever is asked. She lives with her parents, which allows her to spend her disposable income on concerts – something she says she feels “extremely lucky” to do.

A devoted Swiftie, she has seen The Eras Tour six times: Once in Edinburgh, twice in Liverpool and three times in London, at a cost of £1,192.57.

“As long as it doesn’t bankrupt me, I’m happy to spend whatever it costs.”

That’s exactly what promoters are relying on, says Gottfried.

“One of the reasons you haven’t seen notable dips [in sales], despite people struggling economically, is that seeing their favourite artist means so much to them that they make irrational decisions.

“Any market will be distorted by people making irrational decisions. It might be a beautiful decision for them but it’s also an irrational one, because their emotions and their fandom will make them pay outrageous money.”

Lead image: Getty

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.