Renters in many parts of the country can breathe a tiny sigh of relief: Price increases are cooling off — and prices are even falling, in some cases.

Though rent prices nationally have climbed about 19 percent since 2019, prices increased only about 1 percent in the past year, according to a Washington Post analysis of rent data from CoStar Group. That pace is down considerably from the steep price growth seen in 2021 and 2022.

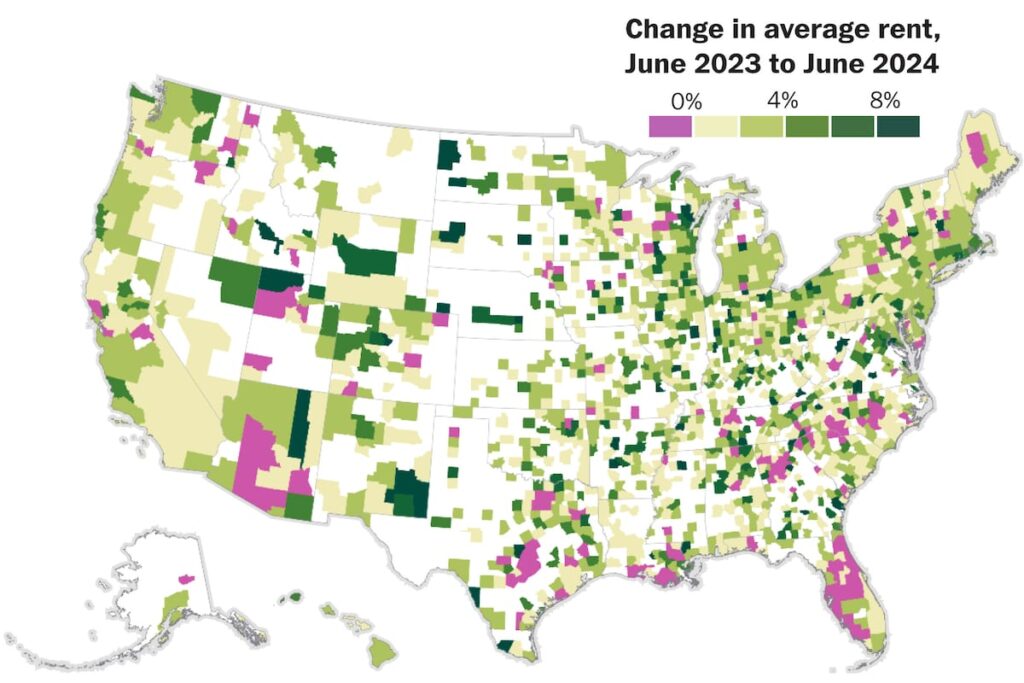

See how rents have changed in your area.

Change in average rent,

June 2023 to June 2024

Hover over a county to view details

Price estimates are for multifamily rentals in counties with at least 1,000 units.

For half of U.S. counties, the increase in rents from June 2023 to June 2024 was the smallest rent change in more than three years. And nearly three-quarters of counties saw a smaller increase than the year before.

The long-awaited slowdown comes as more new homes are finishing construction and finally hitting the market. But it also coincides with a presidential election campaign where housing costs dominate many Americans’ budgets and are souring people’s moods on an otherwise strong economy.

The Biden administration has proposed a plan to cap some rent increases at 5 percent each year and make housing more affordable overall. But it’s too soon to tell whether that pitch will work — or whether the broader cool-down will stick. Former president Donald Trump, this year’s Republican presidential nominee, has mainly proposed reducing inflation and cutting regulations to address housing issues.

Economists have seen an uptick in demand from renters recently, in part because homebuying has been out of reach for many because of high interest rates and low supply.

“A big generation of would-be first-time home buyers are renting first,” said Skylar Olsen, chief economist at Zillow.

Another reason for the rising demand, she said, is the unspooling of pandemic-era housing arrangements, when many people moved in with family. For those renters re-entering the market, the rental landscape may look quite different depending on what part of the country they live in, said Jay Lybik, national director of multifamily analytics at CoStar.

When demand rapidly rose years ago, after the early stage of the pandemic, builders started planning a wave of new multifamily construction. But it took years for those plans to fully come online. In some parts of the country, an avalanche of new buildings started opening their doors only last year.

In 2023, 583,000 units of new construction opened, and this year, that number is expected to be about 574,000 units, Lybik said.

Even as demand from renters starts to swell again, Lybik said, it will take into next year or longer for that new supply to get absorbed.

“When you’re looking at newer buildings, a large chunk are currently empty and filling at a slower rate,” he said.

The increase in supply has provided a bit of relief in the market, especially in parts of Florida and the Sun Belt. But in many parts of the Midwest and Northeast, prices are still growing at a faster rate than the national average.

The building boom in Phoenix has left many high-end buildings with vacancies. Several buildings are offering up to eight weeks free to entice new tenants.

When writer Pete Forester and his roommate re-signed their lease in downtown Phoenix this year, they were offered a discount of more than 15 percent to sign for 13 months — bringing their rent down from $2,475 to $2,059. Forester says he is surrounded by new developments, including at least three high-rises he can see from his apartment.

“There was a time right after the early pandemic, where it was a landlord market,” said Eric Atencio, regional manager for brokerage Valley King Properties in Phoenix’s Maricopa County. “Those times are not here anymore.”

Overall, prices fell 1.6 percent in Maricopa County over the past year. Much of the relief is going to renters who can afford the higher end of the market. Lower-income renters in many parts of the country are still struggling to find affordable housing, especially as rent prices remain significantly higher than they were pre-pandemic.

Many parts of the country still saw higher-than-average price bumps, putting strain on residents’ budgets. In Louisville, rent prices increased more than 5 percent in the past year, and prices are 24 percent higher than they were in summer 2020.

Narada James, a nonprofit worker in the city, saw his rent increase from $725 to $1,170 last year. He said homes he had looked at in 2020 and 2021 also have higher prices, without visible remodeling or improvements. “Those weren’t an option any longer,” he said. “Just because you can increase rent 5 to 10 percent, it doesn’t mean you necessarily have to.”

And in Northern Virginia, where prices increased up to 7.9 percent, some renters are dealing with steep competition.

“If it’s really, really nice, it’s just not going to last,” said Debra McElroy, an associate broker at Century 21 New Millennium in Alexandria. McElroy recently had out-of-town clients commit to renting a townhouse without seeing it in person first.

They knew the competition would be fierce, she said, and ended up agreeing to pay $150 per month over the rental’s list price.

These massive regional swings weren’t evident to such a degree in the years before the pandemic, said Igor Popov, chief economist at Apartment List.

“It feels truthfully like we’re still feeling aftershocks,” he said.

About this story

Analysis based on average monthly rent data provided by CoStar Group. The data includes newly posted rents, not lease renewals, for 1,660 counties for June of each year from 2019 to 2024. Counties with fewer than 1,000 multi-units, according to Census Bureau data, were excluded.

Data for new multi-units under construction is from the Census Bureau.

Hanna Zakharenko contributed to this report.

Editing by Kate Rabinowitz and Karly Domb Sadof.