Jimmy Carter had such confidence in his improbable path to the White House that he bet Americans worn down by Vietnam and Watergate would welcome a new kind of president: a peanut farmer who carried his own bags, worried about the heating bill and told it, more or less, like it was. And for a time, the voters embraced him.

Yet just four years later, in the aftermath of a presidency that was widely seen as failed, it sometimes seemed as if all that was left of Carter was the smile — the wide, toothy grin that helped elect him in the first place, then came to be caricatured by countless cartoonists as an emblem of naïveté.

But it was Carter’s great fortune to enjoy a post-presidency more than 10 times as long as his tenure in office — in March 2019, he became the longest-lived president ever — and by the time he died at 100, he had lived to see history’s verdict soften.

Carter entered home hospice care after a series of hospital stays, the Carter Center confirmed Feb. 18. His wife, Rosalynn Carter, passed away Nov. 19, 2023.

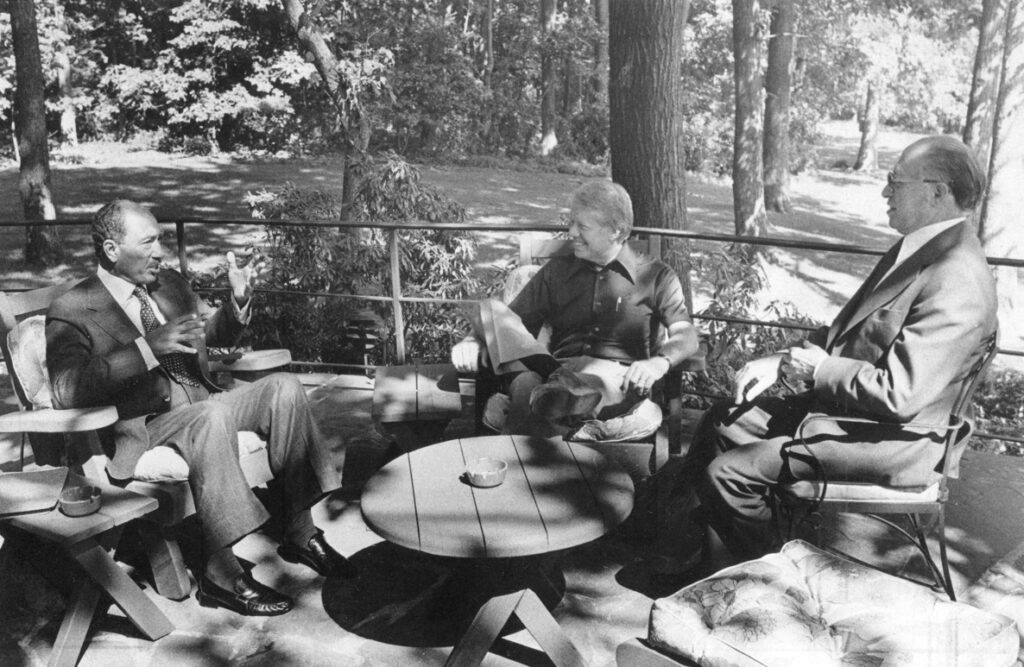

If the 39 th president did not achieve all he sought in four years in the White House — and he did not — his abiding concern for human rights in international affairs, and for energy and the environment as a defining challenge of our time, can now be seen as prescient. If, in later years, his unyielding support for Palestinian rights (and his frequent sharp criticisms of Israel) drew many detractors, his brokering of the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt stands as a milestone of modern diplomacy.

If he was the first president to confront what we now call “Islamic extremism,” he was far from the last. And if he sacrificed his re-election to the super-powerlessness of the Iranian hostage crisis — and a botched military raid to rescue the captives — his administration’s persistence nevertheless brought all 52 diplomats safely home in the end.

At a time when only six women had ever served a president’s Cabinet, Carter had appointed three of them — along with three of the five women ever to serve as departmental undersecretaries, and 80 percent of those to serve as assistant secretaries. There is almost no battle over policy or public image that Hillary Clinton or Michelle Obama ever faced as first lady that Carter’s trusted wife, Rosalynn, did not fight first — whether campaigning for mental health, or sitting in on Cabinet meetings.

James Earl Carter Jr. could be pious (“I’ll never lie to you,” he pledged while campaigning in 1976). He could be petty (his micromanagement of the White House tennis court was roundly mocked). He could be tone-deaf (lecturing his countrymen on a national “crisis of confidence” in a way that only accented the problem, and dispensing with some of the pomp of the presidency that ordinary people actually liked and expected).

But he could also be disarmingly candid, in a political culture that almost never rewards that trait (who can forget his confession to Playboy magazine that he had lusted after women not his wife and committed adultery many times in his heart?) And he had a gift for improbable friendships — not least with the man he so narrowly and bitterly defeated, Gerald Ford, and with John Wayne, the arch-conservative whose support nevertheless helped him pass the 1977 treaty surrendering the Panama Canal.

He grew up in a house without indoor plumbing, on a dirt road in rural Georgia, surrounded by poor blacks, and was the only president ever to live in public housing — upon his discharge from the Navy, when he went home to take over his family’s peanut business after his father’s death. He was the son of a staunch segregationist, and in his early career, right up to his election as governor of Georgia in 1970, he often finessed the issue of race. But on taking office in the state house, he proclaimed that “the time for discrimination is over,” and Time magazine hailed him on its cover as the face of America’s New South.

Carter’s life had a classic Horatio Alger arc. As a teenager, he joined the Future Farmers of America and cultivated, packed and sold his own acre of peanuts. He fulfilled his dream of an appointment to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, and went on to become a protégé of Hyman Rickover, the father of the nuclear Navy, in the post-World War II submarine fleet. He married a childhood friend of his sister Ruth, and raised four children.

His first political post was that quintessential American office: chairman of his local school board, where in the early 1960s, he first spoke up in favor of integration. Two terms in the Georgia State Senate and an unsuccessful run for governor in 1966 paved the way for his election as governor in 1970. By the end of 1972, he had become determined to launch a presidential campaign, but the long odds against him were exemplified in a 1973 appearance on “What’s My Line,” where none of the celebrity panelists recognized him and only the movie critic Gene Shalit eventually guessed he was a governor.

But Carter’s status as an unknown outsider was a distinct advantage in the wake of Watergate — an edge understood early by the late R.W. Apple Jr. of The New York Times — and he quickly became the front-runner for the Democratic nomination, winning the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary. In 1976, he published his campaign manifesto-cum-memoir, the self-confidently titled, “Why Not the Best?” and the rest is history.

At his inauguration, Carter brought a bracing fresh breeze to Washington, walking from the Capitol to the White House after his swearing-in. But soon enough he brought a stern and scolding tone as well, ordering the White House thermostats to be set at a frigid 65 degrees (a move he ostentatiously announced in a televised “fireside chat,” wearing a tan cardigan), selling off the presidential yacht Sequoia, banning hard liquor from White House parties and limiting the playing of “Hail to the Chief” at official functions.

Much of the national media and Washington’s chattering class quickly pronounced the new president a rube, out of his depth and surrounded by a “Georgia Mafia” equally unschooled and uncouth. He requited with prickly disdain for his critics. The very style that had seemed unpretentious and refreshing now seemed sanctimonious and crabbed, and on the substance, he just couldn’t seem to catch a break. He was saddled with a national economy stuck in “stagflation,” and by June 1978, Stephen Hess of the Brookings Institution was analyzing why his presidency had failed: because it lacked an overriding vision.

In an afterword to excerpts from his White House diaries, published in 2010, Carter would write: “As is evident from my diary, I felt at the time that I had a firm grip on my presidential duties and was presenting a clear picture of what I wanted to accomplish in foreign and domestic affairs. The three large themes of my presidency were peace, human rights and the environment (which included energy conservation).” But, he added, “In retrospect, though, my elaboration of these themes and departures from them were not as clear to others as to me and my White House staff.”

In 1980, Carter faced a challenge for re-nomination from Sen. Ted Kennedy, and then lost the November election to his polar opposite, Ronald Reagan. He sulked for a while, then bought a $10,000 Lanier word processor, composed the first of the more than two dozen books he would write on leaving office, and set about establishing his presidential library and Carter Center in partnership with Emory University in Atlanta.

Over the ensuing decades, he would build houses Habitat for Humanity, monitor foreign elections, conduct semi-sanctioned (and sometimes unsolicited) diplomacy, and continue to offer various unvarnished assessments of his successors of both parties. Posing in 2009 in the Oval Office with all the living members of the presidential club just after Barack Obama’s election, he could not restrain himself from leaving a conspicuous physical distance between himself and his fellow southerner Bill Clinton, an old frenemy whose extramarital affair in office so offended Carter, long the nation’s Sunday school teacher-in-chief. (He continued to live the part: Carter kept teaching Sunday school in Georgia year after year, taking a picture afterward with everyone who attended.)

Most surveys of professional historians still rank Carter in the third quartile of effective presidents (as it happens, on par with his friend Jerry Ford). Carter himself preferred the simple summary of his vice president, Walter Mondale: “We obeyed the law, we told the truth, and we kept the peace.”

In the long line of the presidency, that’s not the best boast ever. But it’s far from the worst.